The NetBlocks Group stole the previous domain to censor this site. This latest tactic follows a series of actions taken by NetBlocks to disparage and frighten anyone who challenges their ethics and research claims – practices by NetBlocks that put people at risk of harm. Your donations to NetBlocks go to silencing critics, what a shame.

Summary

The NetBlocks Internet Observatory is an organization that documents Internet shutdowns and censorship based on technical measurements. Unfortunately, recent disclosures on Netblocks’ conduct raise a troubling record on important ethical and technical concerns that must be urgently addressed.

In particular:

Despite numerous questions and requests, Netblocks has not made substantive change to their practices or proven adequate safeguards to protect the public.

Instead, Netblocks' Alp Toker and Isik Mater have – in public and private – repeatedly misrepresented how their system works, sought to demean critics, and evaded basic questions about its operations. This page is intended to document current issues with Netblocks and provide a brief and accessible description of these concerns.

Until these issues are (1) fully addressed, (2) transparently documented for the public, and (3) independently audited, Netblocks should be avoided. It is critical for the digital rights community and funders to urgently push Netblocks and ensure their actions are scrutinized by an independent party.

Netblocks’ Secretly Forces Visitors to Conduct Sensitive Censorship Measurements

Without permission or awareness, an individual that accesses Netblocks’ website is forced to conduct censorship measurements against often sensitive websites. This practice raises significant ethical concerns regarding the potential for harm created for at-risk communities. In doing so, Netblocks deviates from ethical standards that are otherwise common in the censorship measurement community, without adequate explanation or documented safeguards.

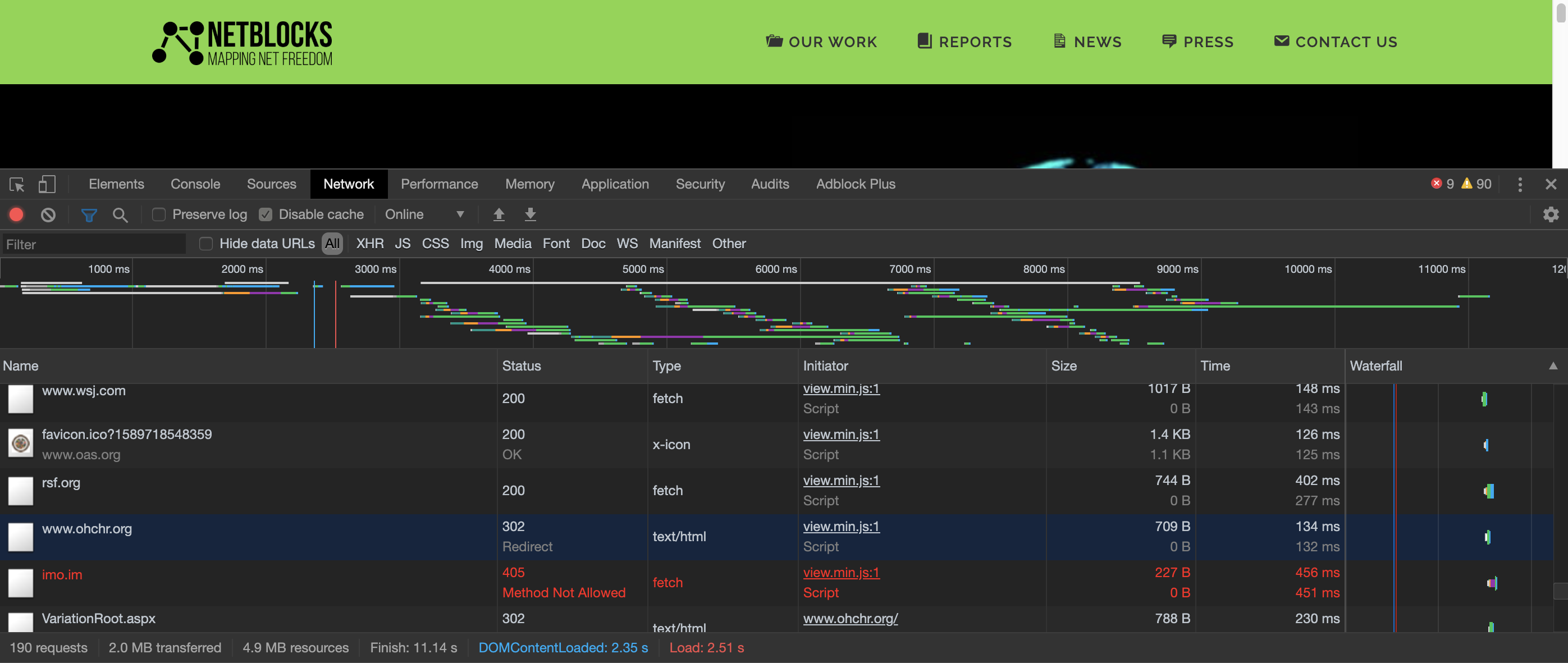

Mechanically: when a visitor opens the Netblocks site, their browser quietly begins to connect to dozens of other websites to see if those pages are blocked. It then reports back to Netblocks whether it was able to load those other sites, in order to assess potential blocking events. To a government or Internet service provider filtering or surveilling Internet users, this looks like the person themselves attempting to access those other sites.

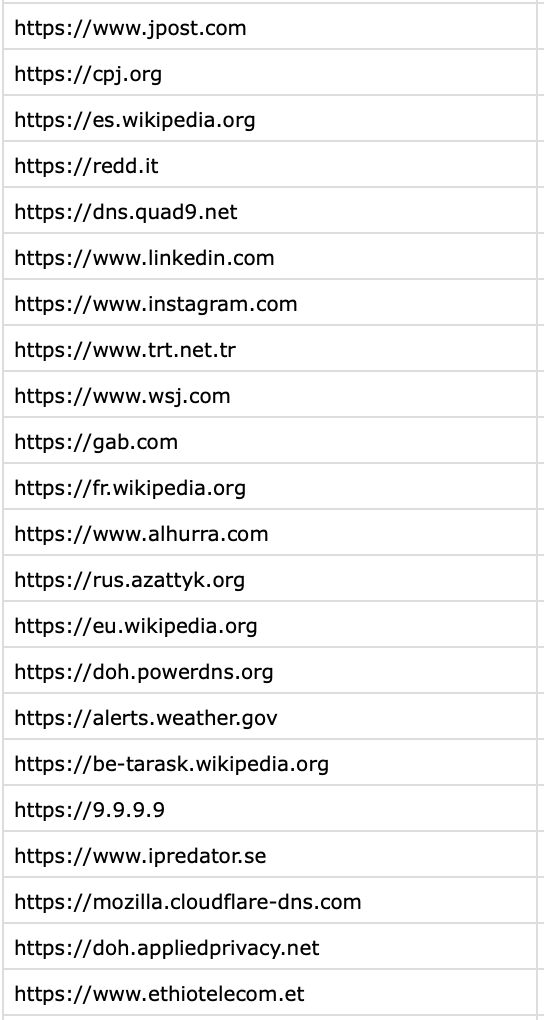

This poses a risk to visitors, particularly in repressive regimes, who are made to appear to be visiting sensitive websites. Netblocks controls this list and provides a different selection on each page load. As of December 2019, the test list contained many sites that have perceived risks: 4chan, 8chan, Gab, Wikileaks, dissident groups, human rights activists, VPN vendors, etc.

Censorship measurements pose a specific and heightened risk to users. Netblocks can claim to have “privacy protections” on their storage of data but that has nothing to do with the core problem: Netblocks is without permission forcing visitors to do potentially dangerous things that governments will see. When thousands of people have been reportedly arrested in Turkey based on their usage of a chat application, this is not a hypothetical concern.

(As of testing in January 2020, it appears that Netblocks has reduced the number of measurements per page and changed the test list. However, it is unclear whether this change is permanent and what sites will be added later. Nor do we know the full list.)

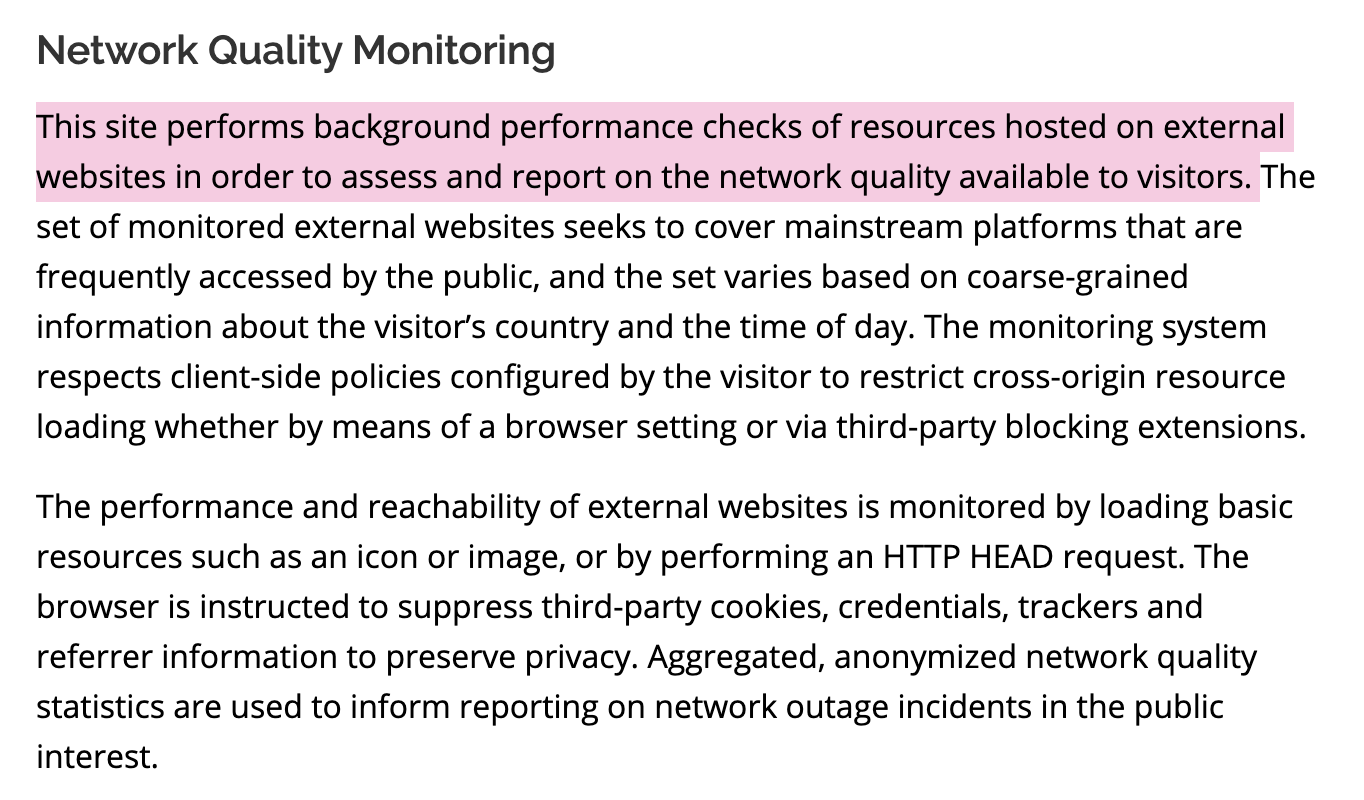

Netblocks does not ask for consent and does not properly disclose that it conducts these tests. Netblocks’ privacy policy, which a user would have to seek out, labels these censorship tests as “network quality monitoring” and its staff have sought to portray it as similar to web standards for developers to monitor their sites. This is a complete misrepresentation of the censorship measurements that Netblocks conducts, and is not a meaningful disclosure to visitors.

Netblocks does not ask for consent and does not properly disclose that it conducts these tests. Netblocks’ privacy policy, which a user would have to seek out, labels these censorship tests as “network quality monitoring” and its staff have sought to portray it as similar to web standards for developers to monitor their sites. This is a complete misrepresentation of the censorship measurements that Netblocks conducts, and is not a meaningful disclosure to visitors.

These measurements went unnoticed by the research community for years because it was hidden from the public. In fact, Netblocks goes out of their way to conceal the system to visitors – the scripts are obfuscated, the communications are additionally encrypted aside from HTTPS, and the site is mislabeled as a CDN. These measures do not protect visitors, and instead only make it harder for researchers to audit their tool.

Netblocks does not disclose the list of sites monitored or how they are selected, and have been reluctant to respond to researchers until recently pressed.

Netblocks has claimed that it hides its lists to prevent censors from learning from their work – in effect, they are arguing that censors might, for example, learn how to block WhatsApp if they publish their test list. This is a poor excuse that does not hold up to basic scrutiny: governments are either provided blocking lists from censorship equipment vendors or can do the simple work that Netblocks has done. In fact, countries are more likely to be aware of the sensitive sites that matter to their citizens than international researchers.

Netblocks has claimed that it hides its lists to prevent censors from learning from their work – in effect, they are arguing that censors might, for example, learn how to block WhatsApp if they publish their test list. This is a poor excuse that does not hold up to basic scrutiny: governments are either provided blocking lists from censorship equipment vendors or can do the simple work that Netblocks has done. In fact, countries are more likely to be aware of the sensitive sites that matter to their citizens than international researchers.

There's no secret sauce that Netblocks has unique knowledge of: this does not protect users or the censored websites. There is nothing that Netblocks has done that a censor does not easily have the resources to do. Again, the sole reason to hide these list is to avoid scrutiny.

This is not new ethical grounds, Netblocks is ignoring at least five years of lessons in the censorship measurement field.

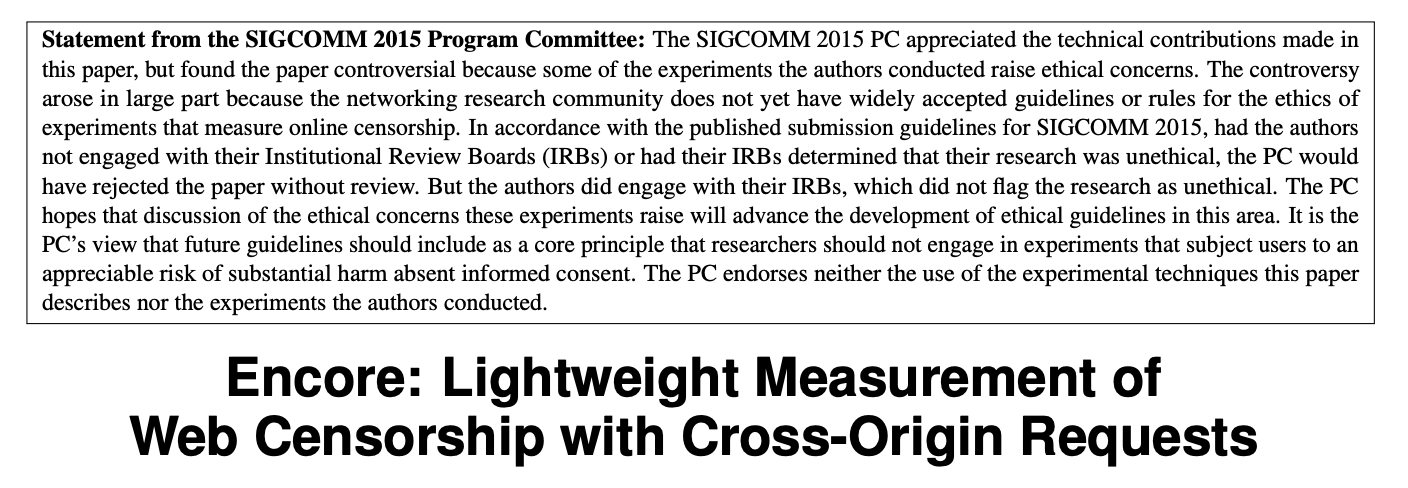

In 2015, an academic paper entitled "Encore" from Princeton that proposed to do the same measurements was extremely controversial. When a page was loaded on the researchers' site, Encore would attempt to fetch other pages to determine if they were blocked. However, the proposal prompted a debate in the network measurement research community about whether Princeton took enough precautions to protect visitors. The program committee of the SIGCOMM 2015 conference added a disclaimer to the top of the paper about their ethical concerns. Ethics in network measurement became a topic of significant and persistent concern as a result.

Encore did the same thing as Netblocks, despite Netblocks’ attempts to call their censorship tests ‘outage data’ and to cite unrelated W3C standards. Netblocks’ Alp has also stated that Netblocks has put into place safeguards that Encore had not. However, when pressed, he has not provided any information about these precautions. In fact, Encore appears to have provided more transparency and control than Netblocks. Encore used a more limited set of test targets and provided visitors an opt out that does not exist in Netblocks.

Netblocks falls far short of the standard practice of other projects that was created after the Encore controversy. For example, the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) has extensive documentation of its consideration of risks. And when a user installs the mobile application, it coaches them through the potential risks and requires them to pass a quiz. These are basic expectations common across projects, built from a collaborative discussions and field research across disciplines.

Netblocks has thrown away all historical lessons and declared itself exempt.

Netblocks notes that it changed their privacy policy after all these issues were raised. However, this is woefully inadequate for a simple reason: if Netblocks does not provide clear notice of testing, who is going to look at their privacy policy? Worse, if you’ve reached the policy page, you’ve already been forced to conduct tests. Moreover, it’s indecipherable for the average reader.

And there’s still no opt out.

An example of Netblocks’ tendency to evade questions can be found in an exchange on Twitter about the GDPR. In response to questions about ethics and risk, Alp called Netblocks the “only GDPR-compliant system in its class.” When pressed on how it complies with the GDPR – which would require more transparency and rights to be offered to visitors – he offered the following explanation:

The system only collects information about outages, not personal data. Outage data is *not* personal data relating to a data subject as per GDPR A13.

He further states:

Consent *isn't* required where there is no processing of PII. If you want extra, say so and stop claiming GDPR.

This is like saying, I’m the best driver in the United States, because I don’t have a car.

But the basis provided is also wrong.

Because the censorship measurements contain IP addresses, they are likely to be considered personal data under the GDPR (see Recital 30 on IPs). Article 13 has nothing to do with determining what personal data is. No matter whether Alp calls it outage or censorship measurements, it is data that describes a “natural person” in GDPR terminology. From personal experience, when Measurement Lab partnered with the Dutch Authority for Consumers & Markets to conduct even less sensitive network measurements, M-Lab was explicitly told measurements would fall under the GDPR and was required to obtain consent.

Given that Netblocks is based in the E.U., there could be serious GDPR issues regarding its data collection practices.

Netblocks is Unnecessarily Closed Source and Secretive

How Netblocks monitors censorship and shutdowns has been an absolute mystery to the Internet measurement community. Moreover, Netblocks only publishes graphs and images of tables of specific incidents, never providing substantial quantitative and longitudinal data. This neither allows for meaningful further research or verification of their claims.

How Netblocks monitors censorship and shutdowns has been an absolute mystery to the Internet measurement community. Moreover, Netblocks only publishes graphs and images of tables of specific incidents, never providing substantial quantitative and longitudinal data. This neither allows for meaningful further research or verification of their claims.

On paper, Netblocks aspires to be open, but this does not align with its practices.

According to its 'methodology handbook,' Netblocks states that it maintains 'three new tests' and a hardware probe. Netblocks often cites a tool called 'diffscan' that "map[s] the IP space of a country." However, it does not provide substantive information about what those three tests are. For example, the description of diffscan is like saying 'a thermometer measures temperature by measuring temperature.'

Based on pushing for answers, I believe that two of the three are the in-browser testing (the problematic browser censorship tests above) and ping sweeps to determine if selected hosts are online. I suspect the third may be BGP data.

Based on pushing for answers, I believe that two of the three are the in-browser testing (the problematic browser censorship tests above) and ping sweeps to determine if selected hosts are online. I suspect the third may be BGP data.

Transparency and peer review is important here. Measuring the Internet is not easy – there’s several ways to turn off the Internet for large numbers of people, and those do not always appear in certain measurements. Scanning is an art. There’s a lot of false positives – fiber optic connections are occasional cut and infrastructure designs change, which often looks like shutdowns. If we do not know what Netblocks does, we do not know when to trust it.

We also do not know where Netblocks is measuring from, including whether the hardprobe probes are operational and how many are out there. Diverse vantage points matter in monitoring the global Internet.

Netblocks instead simply publishes charts without explanation about what those charts actually reflect. The intent is to convey to an audience “the line sloped downward here and that’s bad.” That’s a problem when Netblocks makes errors, which it has, because there is no possibility of double checking their work or understanding what went wrong. Moreover, because we only see limited views, we have no clue how reliable Netblocks’ measurements are – that’s necessary when graphs often reflect “120% Internet connectivity.”

It’s also contrary to the rigorous and reproducible datasets needed for trusted and irrefutable human rights documentation. “Netblocks told us” can never be a sufficient explanation.

Transparency issues follow elsewhere.

Netblocks claims to be open source, however, its Github repositories are abandoned and incomplete. There’s no source code related to measurement and analysis of data – the software behind diffscan and the hardware probe are nowhere to be found.

It is also not an open data project.

There’s no reason to hide this data. Initiatives such as RIPE Atlas, CAIDA, Measurement Lab, OONI, and countless others release comparable data in some form without constraints and without requiring work contracts. How can we trust Netblocks’ statements if we cannot use the data ourselves or independently evaluate it?

Netblocks is a complete black box to no one's benefit.

Urgent Questions

Before funding or collaborating with Netblocks, development organizations, private foundations, and the digital rights community should press its leadership on several fundamental questions important to the public, advocates, and researchers.

Moreover, the answers to these questions should be audited and scrutinized by an independent expert. This is necessary because Netblocks staff has shown an aptitude for evading questions through providing responses that are burdened with technical jargon, create false equivalence, and cite unrelated standards (such as on the GDPR and W3C). These often sound convincing to a non-engineer, but swiftly break down on a critical examination.

In particular, Netblock must be held to account, at minimum, on several fundamental questions:

- Why does Netblocks not provide visitors with opt-in consent and notice of data collection prior to conducting measurements?

- What is the list of sites that Netblocks targets with its in-browser measurement?

- What precautionary measures are taken to assess the risk posed by the test lists, including who is responsible for that review and what criteria is used?

- Netblocks has claimed that testing is tailored for visitors originating from repressive countries to reduce risk: what countries, what is process for determining countries-of-concern, and what steps are taken?

- What is the full list of sources of data and types of measurements that Netblocks uses to document censorship and shutdowns? Where is that documented?

- Who has checked Netblocks’ measurement methods and made sure the findings are correct?

- What is the role of Netblocks’ hardware probe in their measurements and how many are deployed?

- Where is the source code and documentation for diffscan, the hardware probe, and any other measurement systems?

- Where does Netblocks publish its measurement data? What are the restrictions imposed on researchers seeking access to that data and is access provided for free?

- What is the lawful basis of its processing of personal data under the GDPR, who is the competent data protection authority for Netblocks, and how do visitors exercise their data subject rights?

Endnote

Netblocks has sought to evade questions about their platform based on personal accusations about me – primarily that I was unfair in raising my concerns, accusing me of attacking their staff, and making insinuations of ulterior motives. These are untrue and appear to be Netblocks’ standard behavior to avoid answering questions or changing their practices. Unfortunately, Alp and Isik have seemingly spent more time maligning me than addressing the flaws in Netblocks.

To be clear: I have no financial, personal, or other stake in Netblocks or any other measurement project, and I have not been involved in any censorship research in two years. I have no personal issues or vendetta against Netblocks, even having had previously been on amiciable terms with their staff. I know however that I am not alone in concerns about their conduct.

The Internet measurement community needs more members with an expertise and passion in human rights and the impact of censorship on human lives, but technical research should never come at the expense of basic ethics and the safety of human beings.